As a teacher, social worker and bridge-builder, Jake Farr is making life better for trans communities in Toronto and Durham

“Congratulations, you’ve just met a trans person.”

That’s how Jake Farr recently responded to one of his students at Centennial College, where he teaches in the Addiction and Mental Health Worker program. After a class discussion ranged into the realm of gender and the difference between cis gender and trans gender, one student put up his hand and admitted he’d never met a trans person. So Farr walked over, shook the student’s hand and opened his mind.

Reflecting back on it, Farr laughs. “The whole class went silent. All I could think was, ‘I’ve done my job. Here I am. I am a trans person. I’ve done my job.’”

Farr is not someone they will soon forget. “The lens I try to bring is to normalize trans people,” he says. “I’m just a person. But I can bring a different lens, so I’m always nudging in that area.”

Farr’s calling his work a “nudge” is modest. From helping establish housing for trans individuals in Toronto to collaborating with community health, municipal and public safety officials across Durham, all while serving as a prominent member of PFLAG Canada Durham Region, he is leading the way when it comes to fostering a healthy and welcoming community for trans people.

Farr got his start in community work when he decided to sell his company and recertify as a social worker. That landed him at LOFT, a United Way–funded agency that provides support to some of the most marginalized individuals in Toronto’s social services sector. At LOFT, Farr’s lived experience of transitioning inspired him to help get the BLOOM program off the ground. A residence in downtown Toronto, BLOOM provides housing and support to people who are transitioning while living with mental health and substance use issues, or who are experiencing or are at risk of homelessness.

Farr’s trans-community advocacy work began at BLOOM, so it was fitting that we started our day with him by meeting one of the residence’s service recipients.

9 A.M.

We arrive at George Brown College, where Farr meets with Diana, a resident of the BLOOM transitional residence and his newly appointed co-chair of the BLOOM support network for Toronto’s trans community. Thanks to BLOOM, Diana was able to find secure housing and an affirming community that gave her the time and space to redefine her identity after her transition.

“BLOOM gave me a pause where I could put my life together,” she says. “I needed the time to figure out who I was aside from transitioning. For example, I got to focus on playing badminton again, which is something I’d thought I had to give up for my transition.”

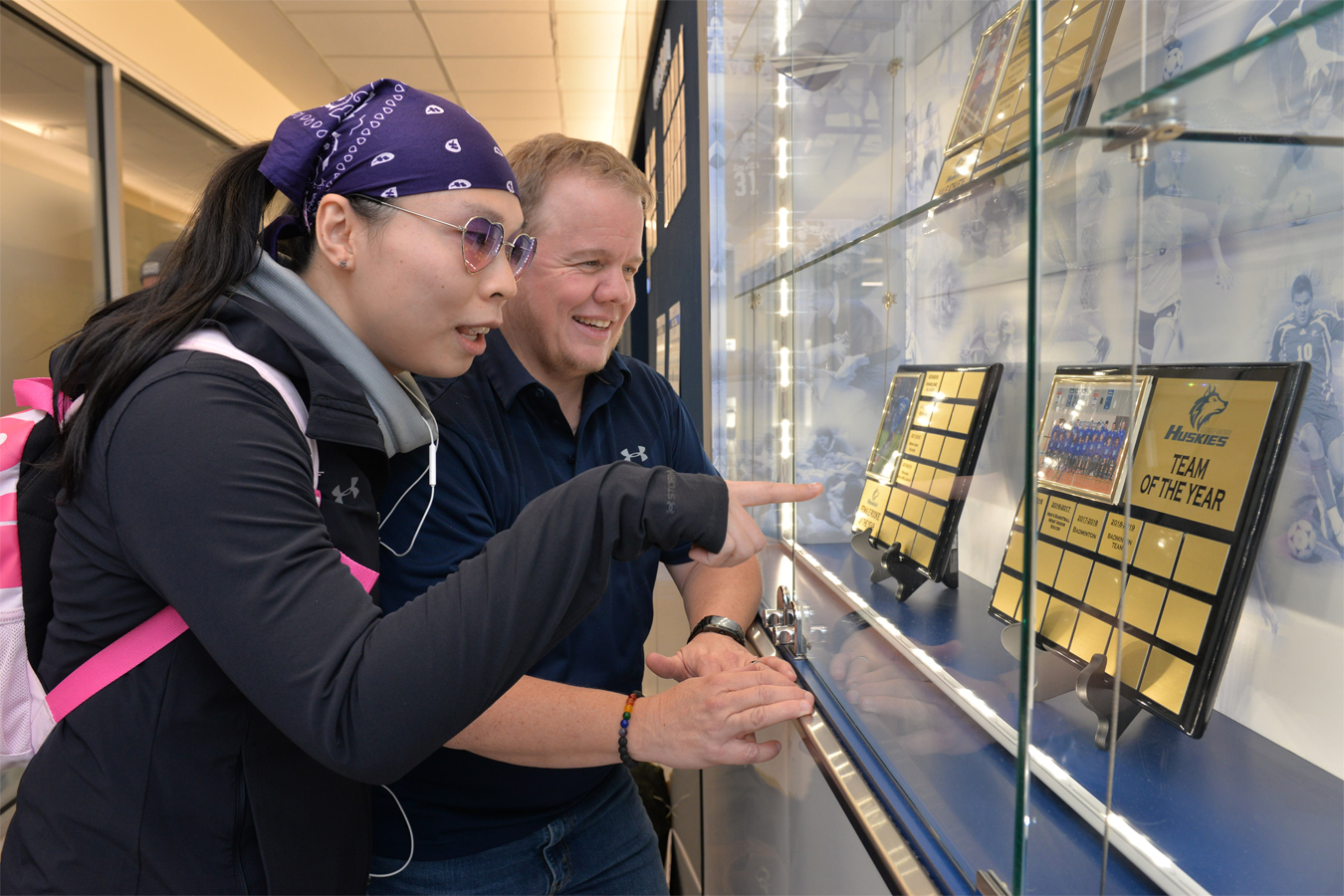

Not only has that return to the sport she loved been great for her mental health, but Diana has also been able to give back to the sport by serving as an advocate for others — she’s the first trans athlete at George Brown College, where she studies. Diana has already met with the college’s vice-president and is working to make changes to varsity league policies to ensure they’re more trans-friendly.

As a symbol of how affirming her return to sport has been, Diana shows Farr her badminton varsity team photo.

10:15 A.M.

Next, we head out to the Region of Durham, where Farr lives. “My work in Durham is mostly about pounding the pavement,” he says. “Compared to Toronto, it is a whole different world. A lot of the gaps in service in Toronto have been filled, but in Durham, we still have those gaps, so I’m working to help fill them.”

In addressing those gaps, Farr has found a strong ally in Pickering city councillor Maurice Brenner, with whom he’s meeting today. On the agenda: discussing how the city’s libraries may be able to support the local homeless population through the cold winter months.

Farr and Brenner started working together when Farr suggested to council that an upcoming city hall renovation should include gender-neutral washrooms. Brenner took up the cause, and the pair has had success after success ever since, putting forward more-inclusive approaches to municipal facilities and services.

Reflecting on their partnership, Brenner singles out Farr’s skill for asking the right questions. “Jake’s not afraid to have those tough discussions that no one wants to have,” he says. “When Jake sees an injustice, he goes into action. That’s where we crossed paths.”

Farr and Benner successfully petitioned to have a rainbow crosswalk installed just outside Pickering City Hall. It now stands as a physical testament to their work in building bridges for the area’s pride community.

And their shared passion for inclusion doesn’t stop there. When some candidates in a recent municipal election were revealed to be supporting hate groups, Farr and Brenner brought together a diverse group of representatives from the community to share their stories of being on the receiving end of those groups’ vitriol.

The forum was a huge success, but Brenner views it in simple terms. “It’s really about learning and changing culture and mindset,” he says. “It’s not that anyone is bigoted or racist in our city hall or anywhere else. Unless you’ve walked in somebody’s shoes, you really don’t get it.”

11 A.M.

Another partner in that community forum on hate was Inspector Jeffrey Haskins. In his role as part of Durham Regional Police’s diversity and inclusion team, Haskins has worked with Farr to try to unite the law enforcement and LGBTQ+ communities.

The police force is particularly interested in creating positive spaces where they can engage with youth, and today’s meeting is about one such initiative: the Colours Youth Group, which is facilitated by Durham Regional Police in collaboration with local health provider Carea Community Health Centre. This monthly meeting allows regional police members with different roles and jobs to mentor local LGBTQ+ youth. “It helps on both sides,” Farr says, “giving the youth a perspective on policing and the police a perspective on the lives of members of the pride community.”

Farr and Haskins also collaborate on the newly formed community safety council for Ajax and Pickering, where Farr serves as a representative for his ward. “Jake brings a valuable perspective and a sensitivity that quite often is overlooked in my opinion—and is necessary,” says Haskins. “That human connection helps us consider the person in question and maintain the dignity of the individual. The authenticity that Jake brings is his superpower,” says Haskins.

11:45 A.M.

Next up is a stop at Carea Community Health Centre, where Farr works part-time as a therapist and peer support worker. In addition to co-facilitating and hosting the Colours Youth Group with Durham Regional Police, Carea’s offices in Pickering are home to a number of other programs that support the local LGBTQ+ community.

Colours is open to youth aged 13 to 18, and while the Prizmya program supports those aged 18 to 29. For the trans community specifically, Carea offers Family TRANSformations, which supports parents and caregivers of people who have come out as trans, as well as Gender Journeys, a peer support group that helps trans young people feel a sense of community by providing them with a safe space where they can discuss barriers or how to come out to their family. Carea staff make sure to have gendered gear on hand, such as binders, prosthetics, jewellery, nail polish, makeup and clothing. These items allow youth to explore their gender identity by providing them access to things they might not be able to purchase when they are dependent on their parents for money.

Today Farr is meeting with Amy Nagel, with whom he works closely on the Gender Journeys program. Amy notes how valuable Farr has been to the program. “Jake came on board as a peer facilitator, contributing his skills as a registered social worker, his lived experience and his go-getter attitude,” she says. “All of these things have been a great help in making a name for Gender Journeys.”

Though they offer a number of programs for trans individuals, Carea is just getting started on offering trans care, and they are glad to have Farr on board to help them in that journey. “Jake was able to encourage us to have a look at our processes to assure that we are as accessible as we think we are,” says Amy. “He gives a voice to people when they don’t think that they can use their own voices.”

1 P.M.

The Oshawa branch of the Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA) is a little farther along on their journey to support trans people in Durham. They have been offering trans care for more than a year now.

“Our first trans patient came to us after undergoing a very significant affirming procedure,” says Stephanie Skopyk, the nurse practitioner lead who has been integral in helping expand trans care. “This individual couldn’t find anyone else to help them. CMHA is built on a foundational belief in health equity and social justice, so when we saw that this person was facing stigma and inequity, we wanted to address that.”

It’s a motivation that Farr can empathize with. He began collaborating with CMHA by doing what comes so naturally to him: giving voice to an instance of inequity. “Sometimes when people from the trans community try to access health care, they don’t always feel like they can give feedback,” he explains. “So sometimes they share that feedback with me, and I can bring those concerns forward on their behalf.”

Skopyk recalls that first meeting with Farr fondly. “We met Jake when he came to give us some feedback about one of his private client’s experiences at CMHA,” she says. “We welcomed that feedback then, and I couldn’t be more pleased with the way our partnership with Jake has come together.” Since taking on their first trans individual, the number of trans clients at CMHA Oshawa has swelled to just over 140, with a four-month waiting list.

Farr explains that three- to four-month waiting lists are typical for providers of trans care, and it speaks not only to the size of the community but also to the need for additional resources. Still, he’s positive about the waiting list at CMHA. “You’ve got a big wait-list because you’ve done it so well,” he says to Skopyk. “The trans community knows they can come here, and the staff will listen to them and help them.”

“It used to be that people from Durham who were transitioning needed to go to Toronto for supports,” he adds. “But not anymore. Now they can get help right here, where they live. I’m very proud to work with Steph, too, because her team is amazing. They’re really helping the community.”

2 P.M.

As Farr works to increase the profile of the trans community in Durham—and to boost the support available to them—he has a pretty good ally in Oshawa Mayor Dan Carter. Farr and Carter met thanks to Farr’s prominent position in Durham’s PFLAG chapter, and quickly discovered that they share some core values, such as a drive to face stigma in the community head-on.

“I have a conservative head, a socialist heart and a lot of liberal friends,” jokes Carter. “I really do connect with the work of people like Jake, who are engaging others to tackle the hard issues that no one wants to talk about, like mental health, addiction and stigma. There’s no reason we should stand idly by and allow stigma to take lives away. We’re a better community than that. When we work together, we can come up with the solutions for hard issues.”

And when it comes to finding those solutions, Carter is all action. “Mayor Carter comes out to all the events,” Farr says. “He really shows up for us and for the community.”

One example was earlier in the week, when Farr arranged for Carter to meet with LOFT CEO Heather McDonald and Senior Director Karen O’Connor to discuss the services they provide in Toronto, and their successes with the BLOOM program. The mayor is eager to replicate those successes in Oshawa by bringing local agencies together to offer the kinds of services LOFT provides in Toronto. As a follow-up to that first meeting, Farr brought a photo book cataloguing the successes of participants from the BLOOM program to share with Carter.

Carter is fully aware of the challenges his community is facing. “It’s unacceptable to me that we have people who don’t have a place to sleep and be warm,” he says. “It’s unacceptable to me that any individual feels not worthy, not accepted and not loved.” But he has a positive outlook about the potential for collaboration with the community agencies Farr represents. “I’m looking forward to the work with LOFT and Carea, and Jake’s leadership, to see how we might be able to solve some of these issues. I’m very hopeful and optimistic.”

3 P.M.

Even with his various community and professional commitments, Farr still makes time to fit in family commitments, like picking up his two youngest sons from school. His family is an integral part of why he works so hard to advocate for diversity and inclusion in Durham: “I want trans people to be out, to be normalized, because so often society makes us feel like we have to keep hiding,” he says. “Every day we get told, ‘You’re not real. You don’t exist. You shouldn’t exist.’ We need to normalize it. We have jobs. We have families.”

His family is also one of his strongest partners in that work. “I’ve been fortunate,” he says. “For all the challenges and barriers I’ve faced, my family has been amazing: my parents, my partner and my kids.”

Farr shares a story of a time he thoughtlessly pointed out another child on the playground to his son and referred to the other child using the pronoun “her.” “My son was right on it,” Farr says. “He scolded me, saying, ‘How do you know it’s a girl? Did you ask them if they’re a girl?’ My kids are better at this than I am!”

6 P.M.

After getting his sons home and fed, at a time when many people have finished work for the day, Farr heads back to the office. Most evenings he sees clients as part of his private counselling practice. As Farr discovered first-hand when undergoing his own transition, it’s exceedingly hard to find therapists with lived trans experience, so most of his private clients are members of the trans community.

He describes this work as helping trans people build the lives and identities they want. “It’s about allowing them the space to approach their transition in a non-linear way,” he says. “We talk about names. We talk about what their pronoun is today. We work at rebuilding their self-worth, because there is so much internalized transphobia.”

Farr also counsels their family and friends. “Sometimes even our biggest supporters—family or friends—still can’t understand what’s going on,” he says. Through Farr’s work with PFLAG Durham, he’s noted that the majority of calls the organization used to receive were from parents and guardians asking for advice on what to do when a loved one came out as gay. However, things have shifted in recent years. Now, most callers are seeking resources to support someone who has come out as trans.

Reflecting on that shift, and on his work with family and friends of trans youth, Farr sees it this way: “People can feel love,” he explains, “so it’s easier for them to empathize with a sexual orientation other than their own. It doesn’t matter if that love is heterosexual or same-sex or the love you feel for your nephew. People get it. But when you start talking about gender, it’s a totally different thing because they’ve never questioned it.”

“That’s the education piece that I try to take on for the trans community,” he adds. “Helping people understand what they haven’t experienced, and making it normal to them.”