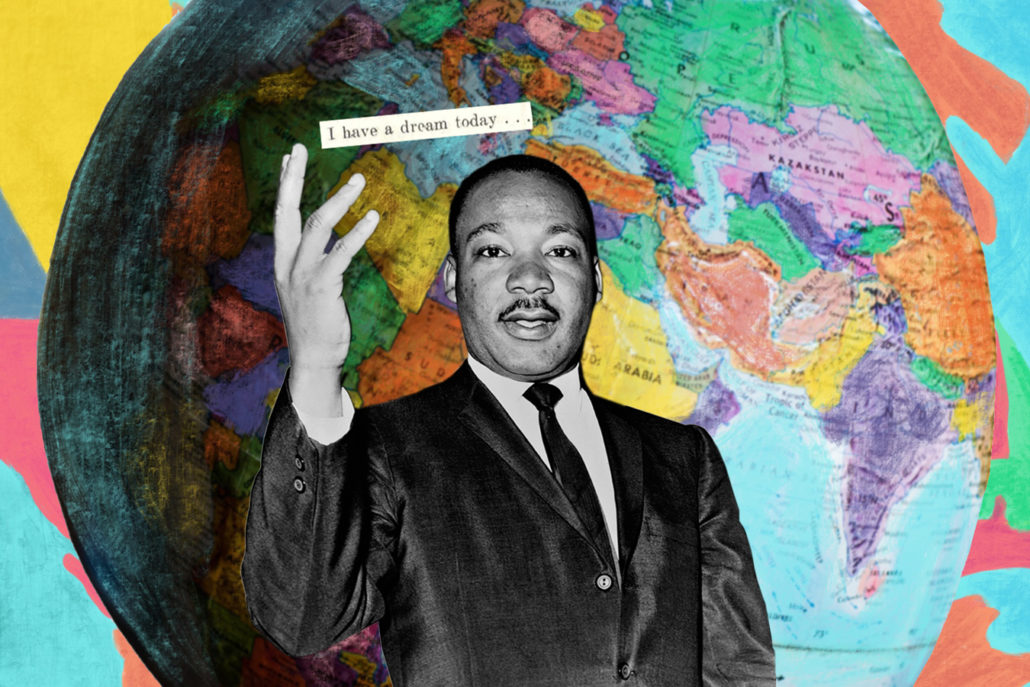

Writer Bee Quammie explains why Martin Luther King Jr.’s words still resonate with Black Canadians

It was 1992, the first Monday in February and my grade four class was filing into school after the morning bell. I rushed to get my coat and snow pants off, tossed my boots under a bench and grabbed my running shoes, then sprinted into my classroom and to my desk as ‘O, Canada’ poured through the intercom. It was, in all ways, an average morning… until the final notes of the anthem floated away and a grand voice boomed across the speakers.

“I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the colour of their skin, but by the content of their character.”

That was the first time I remember hearing the words of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.—and of course it was his “I Have a Dream” speech that ushered in my school’s recognition of Black History Month. King’s powerful words about his dreams for the future have been widely used to inspire the masses—as I was inspired that fateful school day—and have solidified his legacy worldwide. But for Canadians, King’s impact also lies in the way his words speak to our current realities. Today his ideas serve as a roadmap for challenging the prevailing narrative that Canada has historically treated Black Canadians better than our American counterparts—even if that’s a concept he himself perpetuated.

The Black experience in Canada

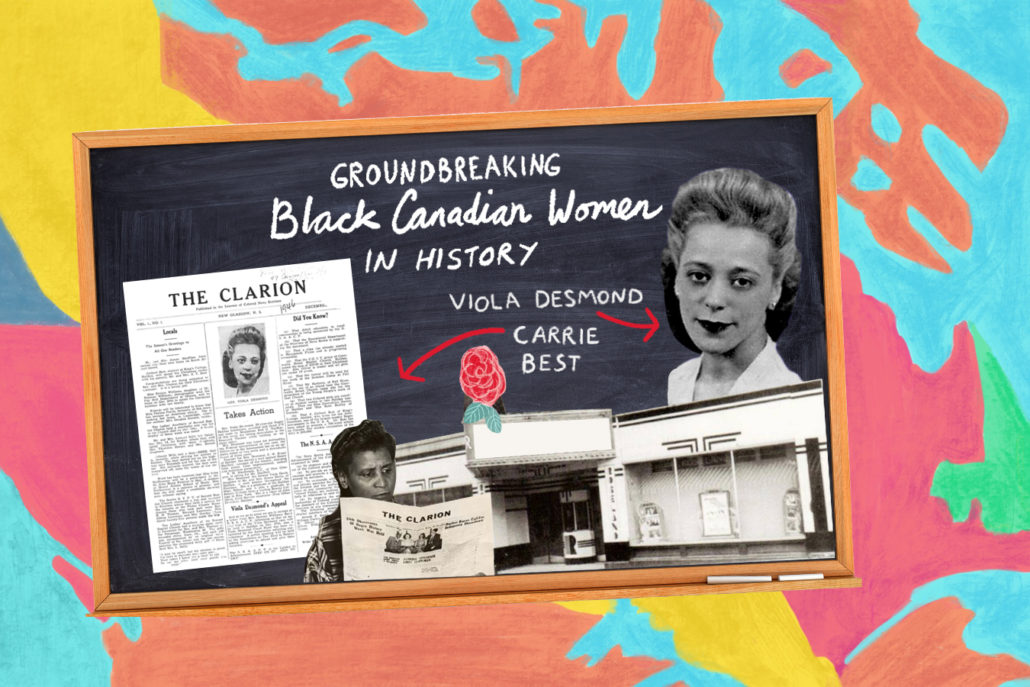

America looms large in all our discussions of race, but particularly when it comes to Black history in Canada. We often focus on figures like King and Rosa Parks—but doing so erases Canadian icons and stories, rendering our contributions invisible. It’s this erasure that helps us to point fingers at the U.S., chiding them for their well-documented accounts of racism and discrimination while ignoring our own.

Unfortunately, that’s something King inadvertently encouraged. In 1967, he was invited by the CBC to give a special Massey Lecture to mark Canada’s centennial, where he said, “Canada is not merely a neighbour to Negroes. Deep in our history of struggle for freedom Canada was the north star. The Negro slave, denied education, de-humanized, imprisoned on cruel plantations, knew that far to the north a land existed where a fugitive slave if he survived the horrors of the journey could find freedom. The legendary Underground Railroad started in the south and ended in Canada. The freedom road links us together.”

King was right: Canada should pride itself on our role in the Underground Railroad. But our generational history is a game of telephone, and we forget that Canada has its own history of enslavement, and what’s more, life after the Underground Railroad hasn’t been perfect for Black Canadians. Take the Africville community in Halifax. For over a century, Africville thrived, even in the face of harsh racism—until it was unceremoniously demolished by the City of Halifax in the 1960s. After the 1988 police shootings of two Black men, Black activists advocated for the creation of Ontario’s Special Investigations Unit—but racially-biased police interactions, from carding to shootings, have continued. And in January of 2018, Prime Minister Trudeau officially recognized Canada’s participation in the United Nations’ International Decade for People of African Descent, acknowledging the anti-Black racism and bias prevalent in all areas of society, from healthcare to the education system to professional industries, including the legal profession.

Without realizing it, King’s Massey Lecture reinforced a one-sided story that sadly still impacts the lives of Canadians, especially Black Canadians, today. But while his words have validated a national story that we’d do well to unpack, they’ve also directly or indirectly encouraged many Black Canadians to speak up and fill in the gaps.

Beyond “I Have a Dream”

Gaps in the story are also common when we think about King himself. The “I Have a Dream” speech—particularly that famous snippet where he talks about that day, still far in the future, where all children will be equal—can paint him in a warm and fuzzy light for those unfamiliar with his history as a fierce fighter for justice. There are also people who twist King’s words and use them to silence those who highlight racism in today’s society. (Those who drag out the slogan #alllivesmatter, for example.)

I’d wager that these individuals haven’t read the full speech—or much of King’s other writings, for that matter. But his less-quoted works are exactly where we should look for inspiration about what’s necessary to fight against injustice and racism today. In his 1963 “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” King wrote about the harsh realities of living in a racist society, and the irony of being considered an “outside agitator” because he fought for equal rights in America. He writes that, “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere,” “freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed,” and that the greatest threat to African-Americans’ freedom is not the violent Ku Klux Klan, but “the white moderate more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice.” And he urges his white readers to understand how imperative it is to act now, that civil disobedience is a necessary tactic and how disappointed he is in their failure to see the urgency in the matter of equality.

As we move forward to a new tomorrow, let’s look at King’s example and ensure we create the society we want to inhabit.

King was assassinated more than 50 years ago on April 4, 1968—but these sentiments are all still alive and thriving, and we see them every time a protest, march or social media hashtag is launched. We should be celebrating the past and present Black Canadian heroes and icons—like Sherona Hall, B. Denham Jolly and Natasha Henry—who have worked to demand equality in a variety of ways. But consider the reactions to the Black Lives Matter Toronto chapter’s sit-down protest and demands of the Pride festival in 2016. Public critique focused more on how BLMTO went about making their demands than the importance of the actual demands themselves. King spoke often about the necessity of disruption in the fight for civil rights, yet here we are, a half century later, leveling the same condemnations against today’s changemakers.

King’s legacy for Canadians is a rich one. From the way his words have shaped the stories we tell about ourselves and our country to the speeches and letters that reflect the actuality of life for many Black Canadians today, his work powerfully forces us to examine ourselves and the world around us. In a 1967 speech aptly titled “Where Do We Go from Here,” King said, “the arc of the moral universe is long but bends toward justice,” reminding the audience that “whatsoever a man soweth, that shall he also reap.” As we move forward to a new tomorrow, let’s look at King’s example and ensure we create the society we want to inhabit. There’s enough work for all Canadians, from those fighting for equality, to those who use their privilege to make room for others, to those who need to unlearn harmful ideologies. Black Canadians and our allies have lived through many traumatic moments in history, and continue to overcome struggles today. But through direct, consistent, and genuine action, the hope is that these positive efforts will bend society’s arc towards the justice we deserve. Because while King is recognized for having a dream, his greater gift is found in the ways he expressed reality—and how we can lean on those words to understand our present and shape a path to a better future.